Project: Marco Zanta Photographs: Marco Zanta Texts: Gabriel Bauret, Giovanna Calvenzi Edited: Massimiliano Bugno, Roberto Koch Graphic design: Stefano Martignago/ms-smart Translations: Contrasto, Roma – Just! s.n.c., Treviso Printed: Graficart, Resana ISBN: 978-88-6965-106-9

More info after the break.

It is not easy to get and accept the wholeness of the linking concept subtended by the word “Europe”.

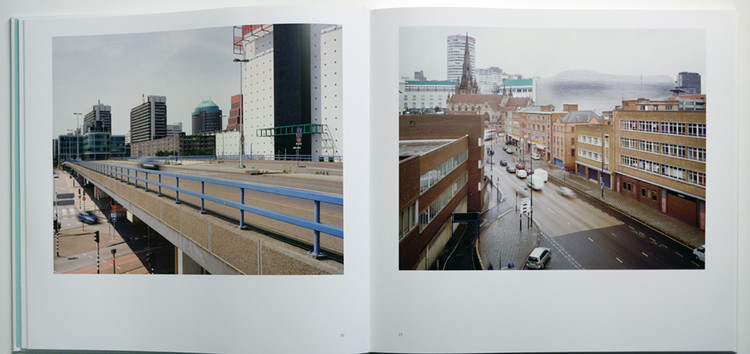

This volume is a high poetical dream: thanks to photography, it’s purpose is to create a composite scenery narrating about a single identity, a possible Europe-city having – despite its being subdivided in separate Countries – an enclosing, recognizable and shareable scale.

Marco Zanta invents this new European city, that one day we will learn to experience as a common country.

Constructing a new city

‘It is the prerogative of photography to capture the multiplicity of forms of the visible world in vivid detail. As the first commentators on the new medium were quick to point out, photography “sees everything and omits nothing”. Yet while photography is capable of pinpoint accuracy and precision, while it focuses and probes its subject with an intensity which can sometimes be uncomfortable, it also has the power to suggest other invisible realities, hidden beneath its minutely described surface.’ These are the opening thoughts of a noted essay (1) written in 1989 by Paolo Costantini, and if this text were a crime novel, Costantini’s statement would provide the main clue, the key to understanding the complex, fluent storyline which Marco Zanta has constructed over the last few years. But let’s not jump to the ending just yet.

The story begins in 2000, when Zanta returned to Italy after a long-anticipated trip to Japan. The photographer had been unsettled by what he had seen and photographed in Japan, by the cities that spread out endlessly for miles and miles, and the experience inspired him to try and gain a better understanding of his own home, roots and cultural background. Zanta has freely admitted that culturally and historically, Italy has an extremely restricted sense of place: even towns and cities in the same region, such as Mestre and Venice or Florence and Prato, regard each other as ‘foreign’, or at least different, and in this context, the idea of a unified ‘Europe’ is hard to understand and accept fully. It is not simply a question of a common currency: ‘Europe’ must somehow unite different countries, cultures and customs; and it is still perceived as an abstract, elusive, intangible concept with fascinating intellectual, social and political implications. Inspired by his love of architecture, Zanta took a keen interest in the numerous architectural projects being planned and executed in various cities across Europe. He embarked on a four-year European odyssey which took him from Helsinki to Lisbon, in search of buildings destined to become modern architectural icons: landmark buildings constructed between 1994 and 2004, which would change the skylines of European cities and be ranked alongside the most prestigious architecture of the world.

By photographing what he saw, Zanta began to ‘build’ his own project: a poetic, dream-like ‘construct’ of a composite city with a single identity, a Euro-city which could really exist, even if in fragmentary form across different countries.

Zanta’s use of stark, bright colour was rooted in the pictorial language of documentary photography, which is both rigorous and fluid. He was aware of the visual experiences of those working in urban environments from the mid-1980s onwards, and was equally aware that the contemporary landscape had been fractured and modified, both conceptually and physically, to the point of being practically illegible. Nonetheless, Zanta remained faithful to the ideals of traditional landscape photography, using them as a framework for exploring fragments of cities: almost as if he were focusing on the virtual – the architectural plans – rather than the physical – the actual building. The outer ‘skins’ of these new-born constructions – be they museums, shopping centres, libraries or offices – were pure and uncontaminated; yet by entering into a dialogue with the existing architecture they left their own unmistakable, often arrogant imprint on the familiar urban landscape, and in turn contaminated it. Zanta wanted to shuffle the pages of perception, to create his own unambiguous vision by ‘building’ a new, ideal kind of city, constructed with elements from other worlds which would either integrate or contaminate, cohabit or fight with the old city structures, themselves frozen in time, preserved in all their beauty or ugliness.

Zanta’s work does not exclude the presence of humans: in the best classical tradition, they help define spaces and architecture. The humans who pass through his images are unconscious observers of the new city being constructed around them: a Euro-metropolis capable of erasing geographical borders, cultural differences and the short-sighted concept of belonging.

Zanta’s photographic project took time, the same time it took for these architectural monuments to modernity to be built, and his response – the construction of his ‘own’ city – became an obsession and, ultimately, an existential and creative imperative. In 2004 he published EUROPAEUROPA (2), his first review of this work-in-progress. At this point he was awarded an arts grant by the Programme Mosaique in Luxembourg, which enabled him to resume his travels and photography, until he was finally able to achieve what Paolo Costantino considered to be the primary objective of photography: to capture with documentary accuracy details of the visible world, while suggesting another, invisible reality; a new reality which exists beneath the surface ‘skin’ of the architecture. Marco Zanta’s dream-like Euro-city gradually materialises in the photographs of this book: a city which pays tribute to the creativity of the architects, and which provides a concrete (although not entirely utopian) vision of a possible future Europe. Zanta reduces Europe to the size of a city, albeit a fictional one: countries shrink and ‘Europe’ becomes a place to be embraced, accepted, and shared. The idea of belonging is born out of a recognised, common cultural environment, and therefore out of a reciprocal understanding and tolerance. ‘Inventing Japan is one way of understanding it’, wrote Chris Marker (3). Marco Zanta found it impossible to invent Japan, and so set about inventing his own new European city, which perhaps we will one day learn to embrace as our common homeland.